PROFOUNDLY PROFANE, JACKAL ELATION, and OTHER RUINED RUMINATIONS

Javier Fresneda and Melinda Guillén in conversation.

Melinda Guillén: We discussed the current iteration of Reología and its placement in a domestic space and how the modes of display, in particular the wine cooler and altered guitar stands, lends itself to a sort of pop cultural approach, distinct from the canonical seriousness of museums. Why is that important to you?

Javier Fresneda: Between 2009 and 2011, my work focused on the representation and visualization of spaces which produced a lot of visual documentation in need of storage, display, and circulation. That made me aware of how, in some cases, documentation takes over the project’s content by means of its format: furniture, grids, diagrams for displaying, etc. I’ve become increasingly allergic to the artistic trend that, by means of formalizing documentation in a ‘serious’ way, dignifies its content even prior to its assessment. So if your project looks pseudo-scientific because of your gray tables, or your wall installation composed by thirty-four images of 35x23” fried eggs, silver pins, etc. you’re on a good track not because of your content, but because how you’ve installed the cutlery on the table nicely. It becomes a question of manners before content.

And then the pop enters. For me, the idea of pop implies the use of emblems that index their own degradation; an accumulation of visual stuff that always indicates its limits, its decay. A pop image always has a specific duration and it’s not a ‘pure’ format that can be transposed indistinctly. It’s not a diagram, but a gesture that wants to talk about itself. So to conceive my visual documentation under the umbrella of pop allows me to look at my images as contours, stains or slices; as a material that you can daub onto things.

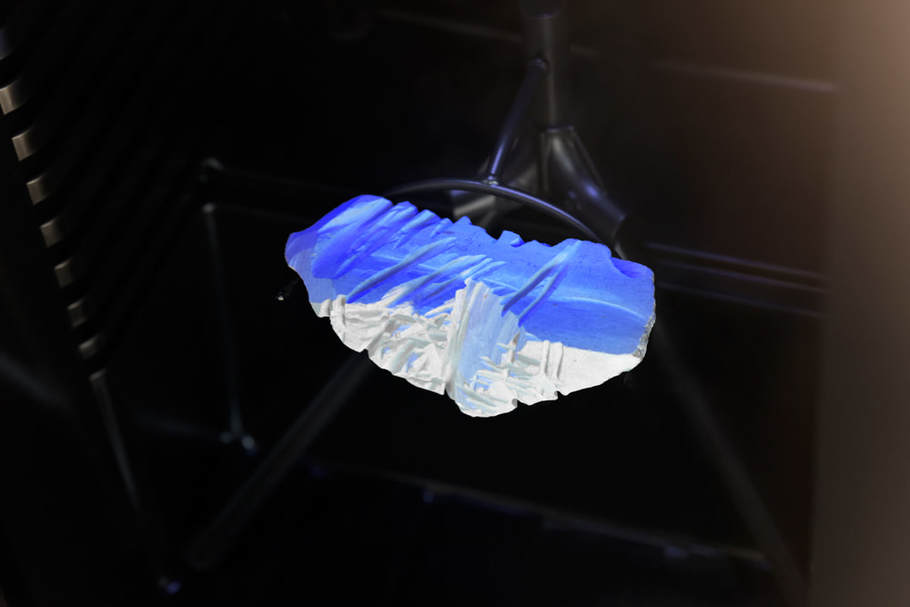

The idea of installing some of my pieces in a domestic space happened after talking with Aitor and Jamie of DXIX Projects. The space has two stories, a basement allocated as a white cubish experience, whereas the second story is an actual apartment. By the time we started talking about the idea of putting a show in the second story it made perfect sense to me; the act of situating my pieces (some of them are furniture) in a given domestic space relocates all the patrimonial matter into a more intimate realm of consumption. The idea was challenging though in the sense of keeping the awareness of the space; trying to not transform the apartment into a white cubish experience, and at the same time to indicate that something is happening there. The use of guitar stands, tables, and coolers creates different degrees of attention and possibility that you wouldn’t get with canonical museum props. For instance, the act of holding pieces or putting them into a cooler vitrine allows you to touch, even steal the artifacts. The table made by Eugenio Encarnación is made of pucté, katalox and zapote. These endemic woods from the Yucatan Peninsula are, in my opinion, actual heritage that in the context of the show become a platform for dirt obtained from canonical heritage sites. We admire the table’s quality insofar as we admit that its role is to display the valuable stuff; little heaps of dirt cut with baking soda. So the incorporation and use of furniture in this way lures us, expanding the scope of experiences in the show.

Javier Fresneda: Between 2009 and 2011, my work focused on the representation and visualization of spaces which produced a lot of visual documentation in need of storage, display, and circulation. That made me aware of how, in some cases, documentation takes over the project’s content by means of its format: furniture, grids, diagrams for displaying, etc. I’ve become increasingly allergic to the artistic trend that, by means of formalizing documentation in a ‘serious’ way, dignifies its content even prior to its assessment. So if your project looks pseudo-scientific because of your gray tables, or your wall installation composed by thirty-four images of 35x23” fried eggs, silver pins, etc. you’re on a good track not because of your content, but because how you’ve installed the cutlery on the table nicely. It becomes a question of manners before content.

And then the pop enters. For me, the idea of pop implies the use of emblems that index their own degradation; an accumulation of visual stuff that always indicates its limits, its decay. A pop image always has a specific duration and it’s not a ‘pure’ format that can be transposed indistinctly. It’s not a diagram, but a gesture that wants to talk about itself. So to conceive my visual documentation under the umbrella of pop allows me to look at my images as contours, stains or slices; as a material that you can daub onto things.

The idea of installing some of my pieces in a domestic space happened after talking with Aitor and Jamie of DXIX Projects. The space has two stories, a basement allocated as a white cubish experience, whereas the second story is an actual apartment. By the time we started talking about the idea of putting a show in the second story it made perfect sense to me; the act of situating my pieces (some of them are furniture) in a given domestic space relocates all the patrimonial matter into a more intimate realm of consumption. The idea was challenging though in the sense of keeping the awareness of the space; trying to not transform the apartment into a white cubish experience, and at the same time to indicate that something is happening there. The use of guitar stands, tables, and coolers creates different degrees of attention and possibility that you wouldn’t get with canonical museum props. For instance, the act of holding pieces or putting them into a cooler vitrine allows you to touch, even steal the artifacts. The table made by Eugenio Encarnación is made of pucté, katalox and zapote. These endemic woods from the Yucatan Peninsula are, in my opinion, actual heritage that in the context of the show become a platform for dirt obtained from canonical heritage sites. We admire the table’s quality insofar as we admit that its role is to display the valuable stuff; little heaps of dirt cut with baking soda. So the incorporation and use of furniture in this way lures us, expanding the scope of experiences in the show.

MG: We’ll get back to the drug part soon. But first, how did you start chiseling pieces of national monuments?

JF: I guess it was in 2012, at the time I was working as Associate Researcher at Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY, Mexico) in the Heritage Conservation Department. I met and still stay in touch with scholars and artists from the area, made some friends and also visited archaeological sites and heritage buildings in different estados de Mexico such as Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Mexico state and Oaxaca to name a few.

MG: Where did the idea to chisel come from?

JF: It arose throughout my frequent visits to those sites and buildings; in retrospect I see Reología as a natural consequence of these experiences. Also, the discovery of Charles Robert Cockerell’s The Professor’s Dream (1848) had a remarkable impact on me. The drawing depicts a landscape filled up with disparate ruins and architectures that vanished into thin air, as if the extension of these buildings continued into a state of suspended dirt.

MG: This reminds me of something from the famed 1928 text “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin”, where Alois Riegl explained that monuments are “erected for the specific purpose of keeping single human deeds or events alive in the minds of future generations.” He felt that each have an imperative, stating that, “[a] work of art is generally defined as palpable, visual, or audible creation by man which possesses artistic value; a historical monument with the same physical basis will have historical value.” Does your work have an imperative?

JF: Not in the sense of having a ‘mission’ at least. I like to think of Reología as a first step towards an integral questioning on the need for preserving stuff according to the current institutionalization we have: ownership by means of bureaucracy and office drama, governance via memos and land expropriation… In other words, I like to use the project to discuss a simple point: the urge for impeding change when it comes to these material traits.

Most of the commonsensical discourse defending heritage’s assets (identity, economy, culture) emphasize materiality and locality in order to conceal that, ultimately, the value of heritage is never embedded into its objects; we can’t have a pound of ‘Mayan culture.’ The value is rather produced without these objects, mainly through vertical mobilizations of documents. And so, a monument not only displaces preexisting heritage, it mystifies the genesis of its value (a room somewhere in Europe) by reclaiming rights of origin.

MG: I bring this up not because I care a lot about maintaining any quasi-authority of Riegl’s formulation of “monumentality” but more so because I know you’re familiar with the text and I’d really like to get at something beyond the hackneyed circulation of references.

JF: Riegl is probably the first bureaucrat in his field. He was less distracted than other colleagues by the perceptual basis of heritage’s value (style, ornament, the idea of the ‘Classic’) and more concerned about the possibility of ‘mining’ value out of material decay. This is why he wanted to correlate his notions of ‘age value’ with ‘deliberate commemorative value’ avoiding in passing the collision between the former with his third trope of ‘historic value.’ My take on Riegl is that he suspends the given ambiguity of what is found (whether or not the monument was a monument,) and by means of restoration he relocates everything within the same plane of existence. You boil down the meaning of whichever object to restoration; then you start mobilizing value. Riegl’s stock is a diagram of sheer loss; a fabulous reserve of disparate assets that become equalized and valuable insofar as all are in the need of restoration, a process owned only by certain institutions and their minions.

MG: Exactly. The primary operation in formalism is the production and maintenance of codified ideological monuments. After that, I see such canonical figures and the territories they claim-as present day hauntings but in a phantasmagoric yet mundane way.

JF: Yes, I’m totally with you on this point. I would argue that if you push a restoration further enough, you’re actually summoning the phantasm of modern style in its concrete apparition. There’s evidence of that in the restoration of the Martrera Castle in Spain, where the white cube literally takes over the ruin. I like to see this case as a rare instance in which you can have both extremes of the very same manifestation (the ruin and the white cube) at the material level.

MG: So do you ever consider the tendency of chiseling in your practice in ritualistic or even quasi-spiritual terms?

JF: So far it’s been an exploration on the notion of value. Part of my curiosity tries to understand what happens with these materials after being deprived of their given form, and to what extent they are still valuable. It points also to the ancient, somewhat unsolved question about the leap from quantity to quality: how much you can subtract from, say, a pyramid before it ceases to be a pyramid.

MG: Is it an addiction or only for recreational purposes?

JF: It starts from a realization of art as a hobby; as a passion that occurs outside thought whenever I’m not at my job.

JF: I guess it was in 2012, at the time I was working as Associate Researcher at Universidad Autonoma de Yucatan (UADY, Mexico) in the Heritage Conservation Department. I met and still stay in touch with scholars and artists from the area, made some friends and also visited archaeological sites and heritage buildings in different estados de Mexico such as Yucatán, Campeche, Quintana Roo, Mexico state and Oaxaca to name a few.

MG: Where did the idea to chisel come from?

JF: It arose throughout my frequent visits to those sites and buildings; in retrospect I see Reología as a natural consequence of these experiences. Also, the discovery of Charles Robert Cockerell’s The Professor’s Dream (1848) had a remarkable impact on me. The drawing depicts a landscape filled up with disparate ruins and architectures that vanished into thin air, as if the extension of these buildings continued into a state of suspended dirt.

MG: This reminds me of something from the famed 1928 text “The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin”, where Alois Riegl explained that monuments are “erected for the specific purpose of keeping single human deeds or events alive in the minds of future generations.” He felt that each have an imperative, stating that, “[a] work of art is generally defined as palpable, visual, or audible creation by man which possesses artistic value; a historical monument with the same physical basis will have historical value.” Does your work have an imperative?

JF: Not in the sense of having a ‘mission’ at least. I like to think of Reología as a first step towards an integral questioning on the need for preserving stuff according to the current institutionalization we have: ownership by means of bureaucracy and office drama, governance via memos and land expropriation… In other words, I like to use the project to discuss a simple point: the urge for impeding change when it comes to these material traits.

Most of the commonsensical discourse defending heritage’s assets (identity, economy, culture) emphasize materiality and locality in order to conceal that, ultimately, the value of heritage is never embedded into its objects; we can’t have a pound of ‘Mayan culture.’ The value is rather produced without these objects, mainly through vertical mobilizations of documents. And so, a monument not only displaces preexisting heritage, it mystifies the genesis of its value (a room somewhere in Europe) by reclaiming rights of origin.

MG: I bring this up not because I care a lot about maintaining any quasi-authority of Riegl’s formulation of “monumentality” but more so because I know you’re familiar with the text and I’d really like to get at something beyond the hackneyed circulation of references.

JF: Riegl is probably the first bureaucrat in his field. He was less distracted than other colleagues by the perceptual basis of heritage’s value (style, ornament, the idea of the ‘Classic’) and more concerned about the possibility of ‘mining’ value out of material decay. This is why he wanted to correlate his notions of ‘age value’ with ‘deliberate commemorative value’ avoiding in passing the collision between the former with his third trope of ‘historic value.’ My take on Riegl is that he suspends the given ambiguity of what is found (whether or not the monument was a monument,) and by means of restoration he relocates everything within the same plane of existence. You boil down the meaning of whichever object to restoration; then you start mobilizing value. Riegl’s stock is a diagram of sheer loss; a fabulous reserve of disparate assets that become equalized and valuable insofar as all are in the need of restoration, a process owned only by certain institutions and their minions.

MG: Exactly. The primary operation in formalism is the production and maintenance of codified ideological monuments. After that, I see such canonical figures and the territories they claim-as present day hauntings but in a phantasmagoric yet mundane way.

JF: Yes, I’m totally with you on this point. I would argue that if you push a restoration further enough, you’re actually summoning the phantasm of modern style in its concrete apparition. There’s evidence of that in the restoration of the Martrera Castle in Spain, where the white cube literally takes over the ruin. I like to see this case as a rare instance in which you can have both extremes of the very same manifestation (the ruin and the white cube) at the material level.

MG: So do you ever consider the tendency of chiseling in your practice in ritualistic or even quasi-spiritual terms?

JF: So far it’s been an exploration on the notion of value. Part of my curiosity tries to understand what happens with these materials after being deprived of their given form, and to what extent they are still valuable. It points also to the ancient, somewhat unsolved question about the leap from quantity to quality: how much you can subtract from, say, a pyramid before it ceases to be a pyramid.

MG: Is it an addiction or only for recreational purposes?

JF: It starts from a realization of art as a hobby; as a passion that occurs outside thought whenever I’m not at my job.

MG: Are all monuments, in your view, intended to be patriotic? Nationalistic? And do you consider your process of chiseling violent? I am obviously fixated on the chiseling.

JF: I’d say that monuments are indexes of destruction, and the byproduct of death as a constructive force. In the most notorious cases, what we do preserve is the imprint of dusty bureaucracy, generational slavery and the elite’s imagery. We like restoration because in so doing, we’re looping destruction.

Monuments are as much patriotic as a biography can be; here paternalism and patternism go hand in hand. Although no one has ever saw a pattern (nor a father) from the beginning to the end, we insist on keeping a continuous criteria when it comes to material heritage; typologies succeed one after another until they become subsumed by documents. Monuments are also nationalistic as much as they’re nostalgic, you’ve the right to yearn as long as you are an accomplice in the destruction. You can find this symptom in the Yucatán, a place where the elites are proud of the glorious remote Mayan past, whereas the current Mayan legacy is lawn mowing the Country Club’s golf courses. What is left to nationalism are memos for real estate, the tertiary industry so as to the ‘visitor economy’ dress up in guayabera.

As for the looting, it’s funny to note that in most of cases I haven’t been in the need of hitting the building. Either because of the site’s material cohesion, or because some fragments are simple here and there, heaped, you can skip the Indiana Jones part. There’s no violence in the act of vanishing a preexistent human imprint into dirt. Not if it’s valuable in the name of colonial extractivism. Better let it go.

MG: That’s the thing. They’ll crumble on their own anyway, always in a state of deterioration, erected in a state of delusion. I just like the idea of striking the structure but that’s a personal fetish. In terms of material existence, Lucy Lippard discussed Robert Smithson’s somewhat now-overused concept of the “non-site” where he would bring materials, primarily dirt and rocks, into the gallery space as evidence of the “first hand or physical (as opposed to secondhand or pictorial) experience of nature both as art and as independent from traditional art systems” at the time. Lippard saw that as a way of “objectify[ing] a sense of place” and that perspective still holds true today where material is a referent for the “real” thing. However, it seems as though your process of subtraction isn’t merely to present material as a reduced form of the source by way of reference but rather, you intend to reduce aspects of the source—how we perceive it, its authority, its so-called originality, and the often absurd and costly methods of preserving such monuments.

JF: Yep. I would add that the heritage site is the non-site par excellence. It’s the result of a previous displacement of preexisting conditions and bodies that dwelled way before the time of its denomination as patrimony. So the ‘source’ has been lost in the moment of its emulation, which is something that ties to the trope of drugs use. The initial promise of full acceptance (of the self and the others) or the creation of a common understanding becomes dismantled in the very moment of its enactment. The promise is never fulfilled, this is why you have to repeat it over and over. Indirectly, my process reenacts the same displacement with the exception that so far I’m not creating a monument; the promise becomes ingested or snorted and...disappears?

JF: I’d say that monuments are indexes of destruction, and the byproduct of death as a constructive force. In the most notorious cases, what we do preserve is the imprint of dusty bureaucracy, generational slavery and the elite’s imagery. We like restoration because in so doing, we’re looping destruction.

Monuments are as much patriotic as a biography can be; here paternalism and patternism go hand in hand. Although no one has ever saw a pattern (nor a father) from the beginning to the end, we insist on keeping a continuous criteria when it comes to material heritage; typologies succeed one after another until they become subsumed by documents. Monuments are also nationalistic as much as they’re nostalgic, you’ve the right to yearn as long as you are an accomplice in the destruction. You can find this symptom in the Yucatán, a place where the elites are proud of the glorious remote Mayan past, whereas the current Mayan legacy is lawn mowing the Country Club’s golf courses. What is left to nationalism are memos for real estate, the tertiary industry so as to the ‘visitor economy’ dress up in guayabera.

As for the looting, it’s funny to note that in most of cases I haven’t been in the need of hitting the building. Either because of the site’s material cohesion, or because some fragments are simple here and there, heaped, you can skip the Indiana Jones part. There’s no violence in the act of vanishing a preexistent human imprint into dirt. Not if it’s valuable in the name of colonial extractivism. Better let it go.

MG: That’s the thing. They’ll crumble on their own anyway, always in a state of deterioration, erected in a state of delusion. I just like the idea of striking the structure but that’s a personal fetish. In terms of material existence, Lucy Lippard discussed Robert Smithson’s somewhat now-overused concept of the “non-site” where he would bring materials, primarily dirt and rocks, into the gallery space as evidence of the “first hand or physical (as opposed to secondhand or pictorial) experience of nature both as art and as independent from traditional art systems” at the time. Lippard saw that as a way of “objectify[ing] a sense of place” and that perspective still holds true today where material is a referent for the “real” thing. However, it seems as though your process of subtraction isn’t merely to present material as a reduced form of the source by way of reference but rather, you intend to reduce aspects of the source—how we perceive it, its authority, its so-called originality, and the often absurd and costly methods of preserving such monuments.

JF: Yep. I would add that the heritage site is the non-site par excellence. It’s the result of a previous displacement of preexisting conditions and bodies that dwelled way before the time of its denomination as patrimony. So the ‘source’ has been lost in the moment of its emulation, which is something that ties to the trope of drugs use. The initial promise of full acceptance (of the self and the others) or the creation of a common understanding becomes dismantled in the very moment of its enactment. The promise is never fulfilled, this is why you have to repeat it over and over. Indirectly, my process reenacts the same displacement with the exception that so far I’m not creating a monument; the promise becomes ingested or snorted and...disappears?

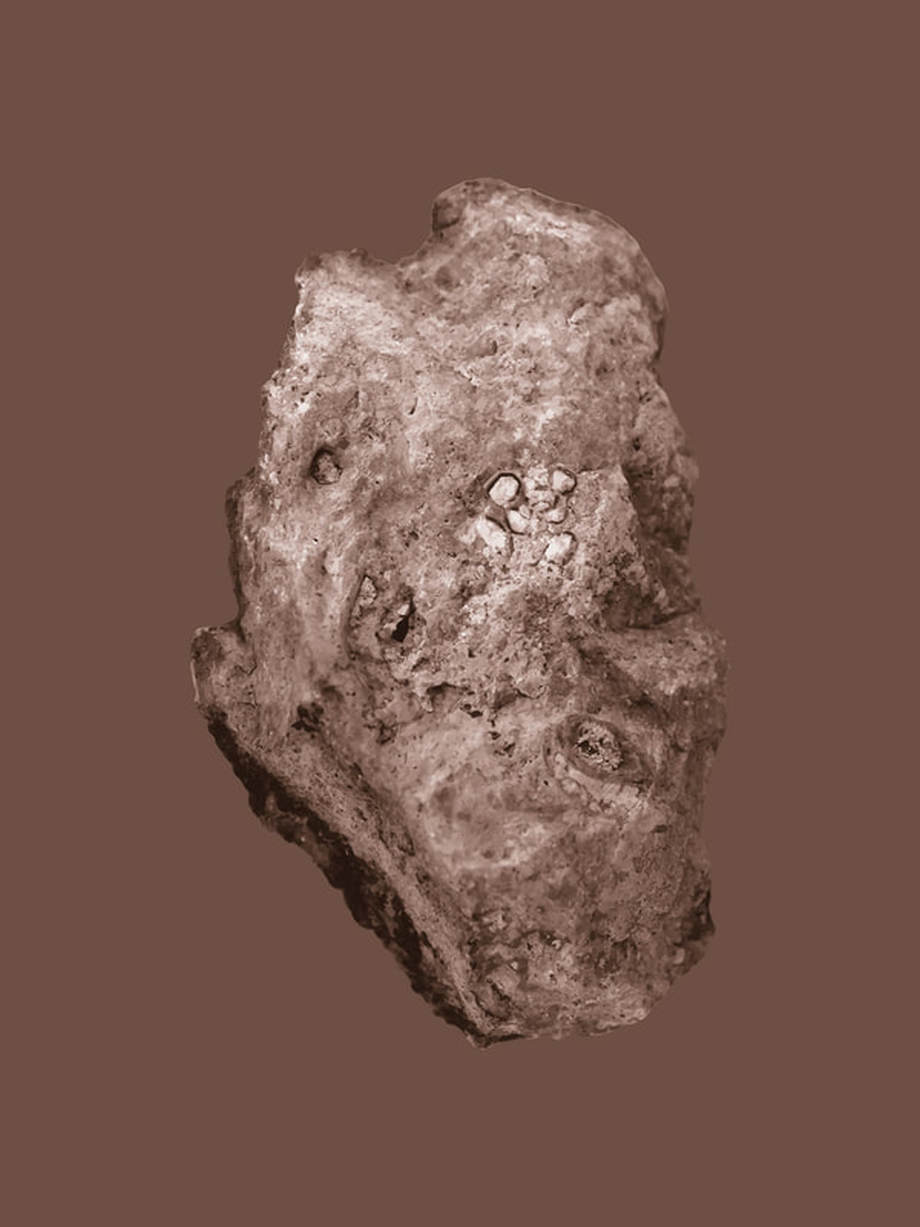

MG: The archeological approach of excavation and extraction of materials is a substantial method in your sculptural work. Can you elaborate a bit on your interests in forensic documentation as reflected in the six sepia photographs?

JF: I think that notions such as ‘dismantlement’ and ‘looting’ are becoming increasingly important in my work. Now I’m trying to comprehend the process not only as what historically creates culture, but the interim between the removal and the filling. The hollowness.

Regarding the pictures, I think these are a reflection of my disgust from the mildness of documental exploitation. Since the beginning it was clear for me that the project should diverts and derails from there. Though I’d images depicting the removal process of every sample, I decided to present instead images of these samples as composite portraiture, rendering every one alongside a suggested dosage that appears overlapped. I’m intrigued about the idea of personifying the stones, turning them into more like a character. And then you start looking stone faces and having your apophenia.

MG: I like the idea of personifying the stones too and the apophenia of possibly associating the forms with something recognizable, sort of like cloud shapes but less whimsical. More sinister too when thinking about forensic photos and the procedural process of death.

JF: There’s something elusive in these portraits, like matter just being ‘delivered’ via FedEx but without a confirmed status. To put it pedantic, it’s aoristic, a preterite time that’s neither ongoing as the imperfect nor relevant as the perfect. It points out to the core of heritage’s perceptual basis: we recognize shapes only after their chiseling. The cognitive labour that articulates matter has been subsumed within the historian’s sapience. We are ‘making sense’ after the stone has been carved, the building erected, etcetera. But once we’ve lost part of the brick’s shape, are we left with just a stone? This sounds obvious but I’d rather invite you to do it and perceive the point of imbalance where ornament gives its way to inorganic matter. That precise instance. In here, it’s pretty clear to me that we appeal to a belief disguised as something else.

MG: Drug dealing?

JF: Surely. We consume stuff coming from who-knows-where that has an arbitrary value and whose circulation relies heavily on rumors. Does it sound familiar?

MG: Absolutely. I’ve always liked the absurdity in your offering of consuming monuments in capsule form and in the same manner of exchange as party drugs. To me, it always seemed like the next logical step in the perverse structural trajectory of late-capitalism into the neoliberal machine. It’s like when “fine” culinary establishments started serving people desserts with pieces of shaved gold to eat.

JF: It’s interesting you say ‘offering’ because the act of giving the capsules away inadvertently forces you to endow them with a function. For me these capsules are a sculptural bloodshed, an exaggerated, de-monumentalized gift that seemingly has no function except being ingested, but, for some reason the gift never ends totally in the sewer. We never get just plain shit. Some people collect them, some are making tales out of them, some others have the stuff just seated elsewhere, ‘hodling’ them...so the capsules force you to give them something back; a new type of endurance. We may close the circle saying that what these capsules encapsulate is not only their matter but their circulation as a public secret “into which all secrets secrete” as Taussig reminds us following Benjamin.

MG: The link between tourism and drugs (or tourism as a drug?) makes a lot of sense to me. They are both enchanting and intoxicating and also often, either disappointing or at the very least, the return to any previous version of normality can be quite harsh. I recall one of Walter Benjamin’s charming and well known experimentations with hashish where he reflected, “A deeply submerged feeling of happiness that came over me afterward… is more difficult to recall than everything that went before.” Is consumption an escape?

JF: I’d say that drugs monumentalize bodies in its closure to death as we’ve discussed before. Death builds a body through intoxication that requires restoration: simultaneous maintenance and dismantlement. You drink some water whilst getting fucked up. Tourism may well be the extension of such intoxication by means of colonial disavowal; the amnesia of being a tourist in spite of what facilitates one’s intoxication, and the nostalgia of not being intoxicated enough. We destroy in order to recall the fracture, not the thing being destroyed.

JF: I think that notions such as ‘dismantlement’ and ‘looting’ are becoming increasingly important in my work. Now I’m trying to comprehend the process not only as what historically creates culture, but the interim between the removal and the filling. The hollowness.

Regarding the pictures, I think these are a reflection of my disgust from the mildness of documental exploitation. Since the beginning it was clear for me that the project should diverts and derails from there. Though I’d images depicting the removal process of every sample, I decided to present instead images of these samples as composite portraiture, rendering every one alongside a suggested dosage that appears overlapped. I’m intrigued about the idea of personifying the stones, turning them into more like a character. And then you start looking stone faces and having your apophenia.

MG: I like the idea of personifying the stones too and the apophenia of possibly associating the forms with something recognizable, sort of like cloud shapes but less whimsical. More sinister too when thinking about forensic photos and the procedural process of death.

JF: There’s something elusive in these portraits, like matter just being ‘delivered’ via FedEx but without a confirmed status. To put it pedantic, it’s aoristic, a preterite time that’s neither ongoing as the imperfect nor relevant as the perfect. It points out to the core of heritage’s perceptual basis: we recognize shapes only after their chiseling. The cognitive labour that articulates matter has been subsumed within the historian’s sapience. We are ‘making sense’ after the stone has been carved, the building erected, etcetera. But once we’ve lost part of the brick’s shape, are we left with just a stone? This sounds obvious but I’d rather invite you to do it and perceive the point of imbalance where ornament gives its way to inorganic matter. That precise instance. In here, it’s pretty clear to me that we appeal to a belief disguised as something else.

MG: Drug dealing?

JF: Surely. We consume stuff coming from who-knows-where that has an arbitrary value and whose circulation relies heavily on rumors. Does it sound familiar?

MG: Absolutely. I’ve always liked the absurdity in your offering of consuming monuments in capsule form and in the same manner of exchange as party drugs. To me, it always seemed like the next logical step in the perverse structural trajectory of late-capitalism into the neoliberal machine. It’s like when “fine” culinary establishments started serving people desserts with pieces of shaved gold to eat.

JF: It’s interesting you say ‘offering’ because the act of giving the capsules away inadvertently forces you to endow them with a function. For me these capsules are a sculptural bloodshed, an exaggerated, de-monumentalized gift that seemingly has no function except being ingested, but, for some reason the gift never ends totally in the sewer. We never get just plain shit. Some people collect them, some are making tales out of them, some others have the stuff just seated elsewhere, ‘hodling’ them...so the capsules force you to give them something back; a new type of endurance. We may close the circle saying that what these capsules encapsulate is not only their matter but their circulation as a public secret “into which all secrets secrete” as Taussig reminds us following Benjamin.

MG: The link between tourism and drugs (or tourism as a drug?) makes a lot of sense to me. They are both enchanting and intoxicating and also often, either disappointing or at the very least, the return to any previous version of normality can be quite harsh. I recall one of Walter Benjamin’s charming and well known experimentations with hashish where he reflected, “A deeply submerged feeling of happiness that came over me afterward… is more difficult to recall than everything that went before.” Is consumption an escape?

JF: I’d say that drugs monumentalize bodies in its closure to death as we’ve discussed before. Death builds a body through intoxication that requires restoration: simultaneous maintenance and dismantlement. You drink some water whilst getting fucked up. Tourism may well be the extension of such intoxication by means of colonial disavowal; the amnesia of being a tourist in spite of what facilitates one’s intoxication, and the nostalgia of not being intoxicated enough. We destroy in order to recall the fracture, not the thing being destroyed.

MG: I think we can end with a bit of Benjamin’s charming tribute to altered states, “And when I recall this state, I would like to believe that hashish persuades nature to permit us for less egoistic purposes-that squandering of our own existence that we know in love. For if, when we love, our existence runs through Nature’s fingers like golden coins that she cannot hold and lets fall so that they can thus purchase new birth, she now throws us, without hoping or expecting anything, in ample handfuls toward existence.” - Walter Benjamin, “Hashish in Marseilles” (1932).

JF: Sometimes I've heard how the obscurity of Benjamin’s texts is excused in the name of his fondness for hashish. “You know, when it comes to writing sometimes you’ve to get stuck.” “You’ve to see Ibiza back in time” etc. Wasting one’s life for the sake of preserving life as such is excusable only if you create, which differs from merely being productive. So we’re welcome to hallucinate further Benjie’s stoned daydreaming because we mimic intoxication together, just like that. Mimesis about mimesis, not about objects being mimetic each other. You may imagine why for some, fixation of meaning is so important when it comes to this question. Meaning can block the freefall. The apophenia (correlation) of interpretation conceals the apophenia that combines shared intoxication.

Let’s derail a bit more: you sculpt a seemingly monstrous goddess of water because you ate your cactus soup and you’re carving a trip whose etiology is less important than the trip’s imprint. Of course, this is the account of an intoxication that may or may well not happened. But between stoned carvers carving stone and the articulation of an imperial imaginary under the aegis of a galactic intelligentsia eventually disguised as mushrooms I’d stick with the former case. I’ve seen that though.

So yes, apophenia once more, but (and this is my point) with different relations of transitivity and quasi-transitivity: sometimes is vague meaning all the way down and sometimes your vague choice interrupts that consensus. That’s the place that I like. For me, it would be the place of carved venuses, cemíes and flutes for dildoing, plugging in and jacking off; the account of these figurines as a result of the occupational therapy of autistic kids and yes, also the account of paleros in helicopter tossing ashes, colonial swords looted from tombs and funerary remnants embedded in a stone with wifi hotspots. Look up.

JF: Sometimes I've heard how the obscurity of Benjamin’s texts is excused in the name of his fondness for hashish. “You know, when it comes to writing sometimes you’ve to get stuck.” “You’ve to see Ibiza back in time” etc. Wasting one’s life for the sake of preserving life as such is excusable only if you create, which differs from merely being productive. So we’re welcome to hallucinate further Benjie’s stoned daydreaming because we mimic intoxication together, just like that. Mimesis about mimesis, not about objects being mimetic each other. You may imagine why for some, fixation of meaning is so important when it comes to this question. Meaning can block the freefall. The apophenia (correlation) of interpretation conceals the apophenia that combines shared intoxication.

Let’s derail a bit more: you sculpt a seemingly monstrous goddess of water because you ate your cactus soup and you’re carving a trip whose etiology is less important than the trip’s imprint. Of course, this is the account of an intoxication that may or may well not happened. But between stoned carvers carving stone and the articulation of an imperial imaginary under the aegis of a galactic intelligentsia eventually disguised as mushrooms I’d stick with the former case. I’ve seen that though.

So yes, apophenia once more, but (and this is my point) with different relations of transitivity and quasi-transitivity: sometimes is vague meaning all the way down and sometimes your vague choice interrupts that consensus. That’s the place that I like. For me, it would be the place of carved venuses, cemíes and flutes for dildoing, plugging in and jacking off; the account of these figurines as a result of the occupational therapy of autistic kids and yes, also the account of paleros in helicopter tossing ashes, colonial swords looted from tombs and funerary remnants embedded in a stone with wifi hotspots. Look up.

Javier Fresneda is an artist and researcher based on the West Coast and the Yucatán Peninsula. His work examines models of materiality, space and heritage in the digital culture. Some of his recent projects have been presented in places and events such as the Museum of Contemporary Art of San Diego (U.S.) Hidrante (Puerto Rico) and Salón Acme #5 (Mexico). He is cofounder of publishing platforms Cocom and Scrolldiving, and a teacher at ESAY (Yucatán, Mexico). He is currently pursuing a PhD in Art History, Theory, Criticism and Art Practice at UC San Diego.

http://fugaciel.com/

http://cocompress.com/

http://scrolldiving.pro/

Melinda Guillén is a writer, curator, organizer, and art historian based in southern California. She specializes in post-war American conceptual art, radical feminism, and spatial theory. In 2017, she co-founded LOUD, a San Diego-based arts collective centering women of color in cultural production and institutional partnerships. She is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at UC San Diego.

http://melindaguillen.com

http://fugaciel.com/

http://cocompress.com/

http://scrolldiving.pro/

Melinda Guillén is a writer, curator, organizer, and art historian based in southern California. She specializes in post-war American conceptual art, radical feminism, and spatial theory. In 2017, she co-founded LOUD, a San Diego-based arts collective centering women of color in cultural production and institutional partnerships. She is currently a Ph.D. Candidate in Art History, Theory, and Criticism at UC San Diego.

http://melindaguillen.com

|

A section dedicated to regular publishing of art essays, interviews and other text based materials related to critical issues in art

and contemporary culture. |