IT'S (NOT) A WRAP

Laida Lertxundi with Ren Ebel

Ren Ebel: Do you want to set the scene?

Laida Lertxundi: We are on a bus going to Bilbao from Madrid. Twenty degrees. Semi-arid landscape.

RE: How did you feel about last night’s screening [Cine Doré at the Filmoteca Española, Madrid]?

LL:It was good. It was very in-depth. Seemed like a focused viewing.

RE:It was my first time seeing your films in Europe. I’ve only ever seen them in Los Angeles.

LL: Yeah, I was thinking something last night when Cry When It Happens was playing. The motel shot, the pink sky, the traffic… I know this place in a different way when I’m far from it. It’s almost more cohesive than when I’m in Los Angeles. I also think about how it’s such a struggle to live there, and how in that struggle is also the making of these films.

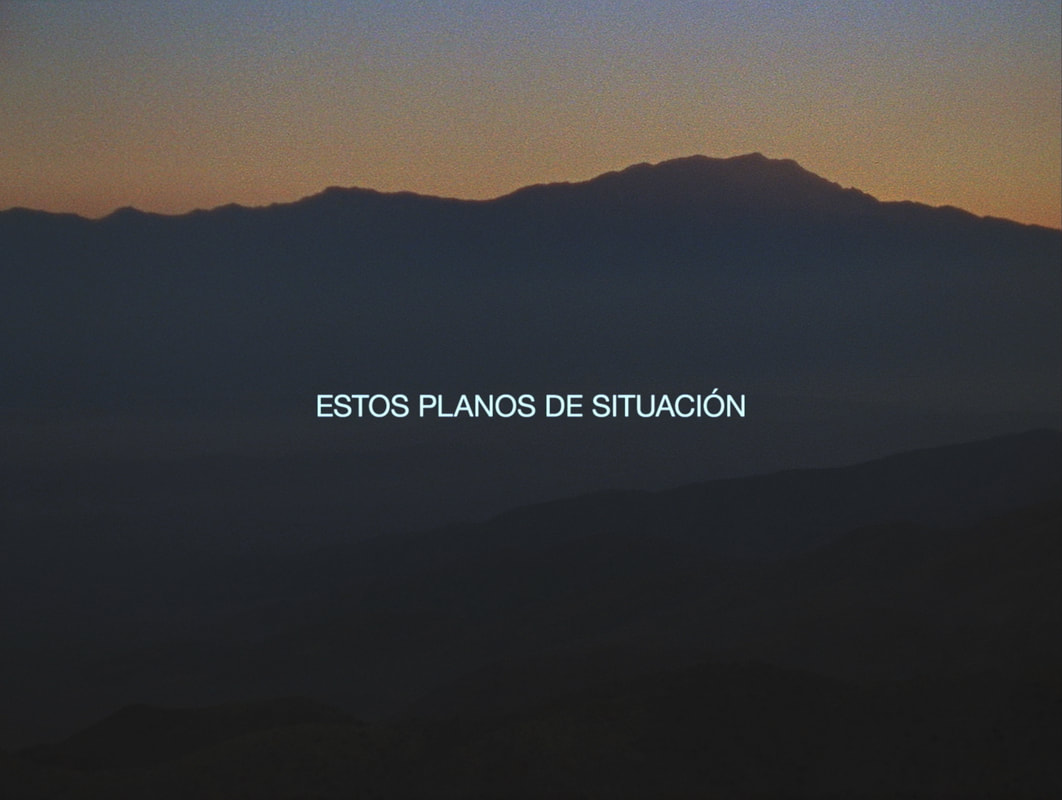

RE: Your films are always compressing and expanding — landscape as an image, and then landscape as an environment. There’s an unfolding of space, and a sudden flattening.

LL: There’s something about that unfolding of a space. [Nathaniel] Dorsky talks about it as empathy. The moment you connect — there has to be enough time, or the right timing, for you to empathize with a shot. I’m creating an environment with some kind of realism — sync sound, ambient sound, all of these things that kind of establish the real in a way — and then you get cut out of the scene, so it’s just an edit, or it’s just an arrangement. I’m interested in that. I think that’s what I mean by “landscape plus.” There is something that’s real, that’s in front of the camera, and then there’s a fiction, an orchestration.

RE: You could almost say, also, “landscape minus.”

LL: [Laughs]Landscape minus, if all these people would just go away.

Laida Lertxundi: We are on a bus going to Bilbao from Madrid. Twenty degrees. Semi-arid landscape.

RE: How did you feel about last night’s screening [Cine Doré at the Filmoteca Española, Madrid]?

LL:It was good. It was very in-depth. Seemed like a focused viewing.

RE:It was my first time seeing your films in Europe. I’ve only ever seen them in Los Angeles.

LL: Yeah, I was thinking something last night when Cry When It Happens was playing. The motel shot, the pink sky, the traffic… I know this place in a different way when I’m far from it. It’s almost more cohesive than when I’m in Los Angeles. I also think about how it’s such a struggle to live there, and how in that struggle is also the making of these films.

RE: Your films are always compressing and expanding — landscape as an image, and then landscape as an environment. There’s an unfolding of space, and a sudden flattening.

LL: There’s something about that unfolding of a space. [Nathaniel] Dorsky talks about it as empathy. The moment you connect — there has to be enough time, or the right timing, for you to empathize with a shot. I’m creating an environment with some kind of realism — sync sound, ambient sound, all of these things that kind of establish the real in a way — and then you get cut out of the scene, so it’s just an edit, or it’s just an arrangement. I’m interested in that. I think that’s what I mean by “landscape plus.” There is something that’s real, that’s in front of the camera, and then there’s a fiction, an orchestration.

RE: You could almost say, also, “landscape minus.”

LL: [Laughs]Landscape minus, if all these people would just go away.

RE: Is compression and expansion something you respond to, or is there another way you think of it? I mean the rhythm your films have, pulling the rug out from under each setup.

LL: Yeah. The other night [Tonino De Bernardi] said that he doesn’t like calling his films shorts. He thinks that’s an insult. In a way I agree. I don’t think of them as short films. Short relative to what? A fourteen minute movie is an epic, you know? So many things happen. I’m trying to create enough variation so there’s an experience of time — like boredom, or elongation and abruptness — an awareness of time that isn’t possible if you only have long takes. Yes, maybe you have an experience of time… But I’m more interested in these changes.

RE: Well there’s a claustrophobia within a certain kind of long take, which I never feel watching your films.

LL: I guess it’s just this desire to be there, to be in the screen, to be absorbed in this world. I think there’s that, and then the interruption. Like, this space doesn’t exist and I can’t take you there. This space is the making of a movie.

RE: I don’t get the feeling that this interruption is like a Brechtian thing, a political imperative. It seems there’s something else that occurs.

LL: I mean, I think there is some of that. Here’s the making of something — that’s very dry, right? But I’m also interested in pleasure. Laura Mulvey wrote about how pleasure needed to be eradicated because narrative cinema had constructed this monster of the male gaze. Talking about process is a kind of deconstruction, and pleasure constructs, makes new worlds. I am interested in feminine jouissance.

LL: Yeah. The other night [Tonino De Bernardi] said that he doesn’t like calling his films shorts. He thinks that’s an insult. In a way I agree. I don’t think of them as short films. Short relative to what? A fourteen minute movie is an epic, you know? So many things happen. I’m trying to create enough variation so there’s an experience of time — like boredom, or elongation and abruptness — an awareness of time that isn’t possible if you only have long takes. Yes, maybe you have an experience of time… But I’m more interested in these changes.

RE: Well there’s a claustrophobia within a certain kind of long take, which I never feel watching your films.

LL: I guess it’s just this desire to be there, to be in the screen, to be absorbed in this world. I think there’s that, and then the interruption. Like, this space doesn’t exist and I can’t take you there. This space is the making of a movie.

RE: I don’t get the feeling that this interruption is like a Brechtian thing, a political imperative. It seems there’s something else that occurs.

LL: I mean, I think there is some of that. Here’s the making of something — that’s very dry, right? But I’m also interested in pleasure. Laura Mulvey wrote about how pleasure needed to be eradicated because narrative cinema had constructed this monster of the male gaze. Talking about process is a kind of deconstruction, and pleasure constructs, makes new worlds. I am interested in feminine jouissance.

RE: There’s something inherently political about the shifts in perspective Mulvey writes about. Like there’s the perspective of the character in the film, and then the camera, and then the audience. Maybe it’s that third shift we’re talking about.

LL: Yeah, I don’t know, that’s a whole other thing, whether you want to call my films political or not. I feel that they are, and I could argue that, but I don’t know if I’d want to. There’s an inherent feminist praxis. Just dealing with the male gaze in cinema, and as a director, if that’s what you want to call me, it’s like being a bull fighter, you know? There are so many wrong moves that get you killed.

RE: So there’s an element of diversion?

LL: What do you mean?

RE: When you mentioned bull fighter, that seemed like a pretty good illustration of the way your films function.

LL: I think you can know you’re being manipulated and still be moved. If I can create this space where people have a certain experience on camera, and the audience has that experience, then that’s enough. It’s kind of subtle and hard to describe. [Bus driver turns the radio up] Is this Bob Marley?

RE: It might be Ziggy.

[Laughs]

LL: Yeah, I don’t know, that’s a whole other thing, whether you want to call my films political or not. I feel that they are, and I could argue that, but I don’t know if I’d want to. There’s an inherent feminist praxis. Just dealing with the male gaze in cinema, and as a director, if that’s what you want to call me, it’s like being a bull fighter, you know? There are so many wrong moves that get you killed.

RE: So there’s an element of diversion?

LL: What do you mean?

RE: When you mentioned bull fighter, that seemed like a pretty good illustration of the way your films function.

LL: I think you can know you’re being manipulated and still be moved. If I can create this space where people have a certain experience on camera, and the audience has that experience, then that’s enough. It’s kind of subtle and hard to describe. [Bus driver turns the radio up] Is this Bob Marley?

RE: It might be Ziggy.

[Laughs]

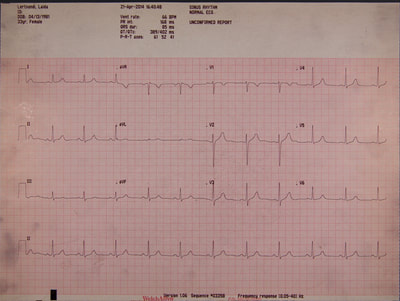

RE: I was thinking about how this accordion pattern which structures your earlier films, the expanding and contracting, becomes a physiological rhythm in Vivir Para Vivir with the heartbeat and the inhale-exhale of the orgasm.

LL: I had worked with bodies in the landscape, and bodies as types of landscape in the past. They were something to film, something that’s exterior. So, I was interested in the body itself as a space for production. The body produces things. There’s something about that title, Vivir para Vivir, Live to Live, that’s kind of existential. Here’s your body and it knows how to work perfectly without the use of your intelligence. So I wanted to document some of that pulse, the fact that it just goes on. And I was interested in several ways that the body could be a structure for a film. You know, getting this image of the EKG, seeing this image as a representation of movement. So there are all these translations of sounds and images. There’s this book I have at my mom’s house in Bilbao, Chaos, Territory, Art by Elizabeth Grosz, that talks about these sort of extra things that happen in nature, during courtship, that are purely aesthetic. Similarly with women’s pleasure, there’s no function. It’s not necessary for the continuation of the species, and the fact that it’s not necessary, I think, makes it more powerful.

RE: It’s like the idea that what makes something art is that it has no use.

LL: Yeah, and how do you even define a woman’s orgasm? Often they’re these waves that can start so far back.

RE: It’s something that’s always there.

LL: It’s another kind of pulse. But because of the presence of the body in that film, the body as a structure — I think it was in Spain, probably someone important said it and then it became the opinion that it was considered a very personal film. But I think it’s definitely my most abstract movie.

RE: Yeah, I feel a return to my own body in an intense way when watching it.

LL: There’s something kind of heavier about Vivir para Vivir. I talked to Ezra [Buchla] when he was working on the sound, and he said something about heavy metal. Like, this heavy bass kind of feeling. It suctions you. It’s also kind of dark.

RE: What you said about aesthetic products of the body reminded me of this interview with Pauline Oliveros from Music With Roots in the Aether where she says something about how her practice is her consciousness, and the music is a secondary product. But I guess with filmmaking there’s less of a direct line to the making. There’s some distance, some amount of planning is necessary.

LL: Someone last night was asking how much in the films is improvised. There are so many good Bresson quotes… “Nothing in the unexpected that is not secretly expected by you.” I know what I want to move towards when I’m working with people, yet I’m not going to direct them. There has to be a certain amount of intimacy and ease and interest in what’s happening. I can’t force it to happen, I can only sort of provide the material means. Like, I’m now going to project this image of a landscape, you sit here, you sit there, play this tape. Then hopefully, for the person doing it, something happens for them, and when I film it, it’s interesting. So I have all my shots planned. With 16mm and sync sound there’s all this orchestration. There’s a feeling that it’s always about to go wrong, and something’s always left to be desired. And with the people in the films, I have no control over their interiority. So I can only attempt over and over again, and then sometimes it works. It’s never like, “that’s a wrap.” It’s not a wrap. [Laughs].

LL: I had worked with bodies in the landscape, and bodies as types of landscape in the past. They were something to film, something that’s exterior. So, I was interested in the body itself as a space for production. The body produces things. There’s something about that title, Vivir para Vivir, Live to Live, that’s kind of existential. Here’s your body and it knows how to work perfectly without the use of your intelligence. So I wanted to document some of that pulse, the fact that it just goes on. And I was interested in several ways that the body could be a structure for a film. You know, getting this image of the EKG, seeing this image as a representation of movement. So there are all these translations of sounds and images. There’s this book I have at my mom’s house in Bilbao, Chaos, Territory, Art by Elizabeth Grosz, that talks about these sort of extra things that happen in nature, during courtship, that are purely aesthetic. Similarly with women’s pleasure, there’s no function. It’s not necessary for the continuation of the species, and the fact that it’s not necessary, I think, makes it more powerful.

RE: It’s like the idea that what makes something art is that it has no use.

LL: Yeah, and how do you even define a woman’s orgasm? Often they’re these waves that can start so far back.

RE: It’s something that’s always there.

LL: It’s another kind of pulse. But because of the presence of the body in that film, the body as a structure — I think it was in Spain, probably someone important said it and then it became the opinion that it was considered a very personal film. But I think it’s definitely my most abstract movie.

RE: Yeah, I feel a return to my own body in an intense way when watching it.

LL: There’s something kind of heavier about Vivir para Vivir. I talked to Ezra [Buchla] when he was working on the sound, and he said something about heavy metal. Like, this heavy bass kind of feeling. It suctions you. It’s also kind of dark.

RE: What you said about aesthetic products of the body reminded me of this interview with Pauline Oliveros from Music With Roots in the Aether where she says something about how her practice is her consciousness, and the music is a secondary product. But I guess with filmmaking there’s less of a direct line to the making. There’s some distance, some amount of planning is necessary.

LL: Someone last night was asking how much in the films is improvised. There are so many good Bresson quotes… “Nothing in the unexpected that is not secretly expected by you.” I know what I want to move towards when I’m working with people, yet I’m not going to direct them. There has to be a certain amount of intimacy and ease and interest in what’s happening. I can’t force it to happen, I can only sort of provide the material means. Like, I’m now going to project this image of a landscape, you sit here, you sit there, play this tape. Then hopefully, for the person doing it, something happens for them, and when I film it, it’s interesting. So I have all my shots planned. With 16mm and sync sound there’s all this orchestration. There’s a feeling that it’s always about to go wrong, and something’s always left to be desired. And with the people in the films, I have no control over their interiority. So I can only attempt over and over again, and then sometimes it works. It’s never like, “that’s a wrap.” It’s not a wrap. [Laughs].

RE: It seems like the new film Words, Planets has a lot to do with splits. There were two completely different versions of the film — one before you gave birth, and one after. And now for the exhibition at LUX you decided to split the film physically between a projection and two monitors.

LL: There’s something about this film that’s so compressed. You’re moving very quickly through a lot of things, the spaces are really dense with references, so I literally wanted to create more space.

LL: There’s something about this film that’s so compressed. You’re moving very quickly through a lot of things, the spaces are really dense with references, so I literally wanted to create more space.

RE: There’s a sort of riddle with the lemons in the film, too. One is fake and one is real.

LL: Yeah, and then two are weird. They look fake.

RE: Oh yeah, the Buddha’s hand lemons?

LL: Yeah. It’s a mysterious film. I was talking to my psychoanalyst about it. I was telling him about [R.D. Lang’s] Knots. There’s the section I use in the film that describes this game being played, and that you’re supposed to play the game by pretending like you’re not playing the game. It’s a kind of perversity. You know, my mom is waiting for me to have this thing called fuste in Spanish, this kind of seriousness of adulthood that should click in at some point. And so as a parent, how do you teach your child to join this game of the social sphere that you

don´t want to play yourself? And in the Lucy Lippard book [I See/You Mean], there are all these possibilities of ways to play that game, or to be unable to play it.

RE: There are choices. You can harden yourself like the fake lemon, or you can get squished. And in viewing the installation you could choose not to read the text on the monitors, for example.

LL:Yeah, that’s how I wanted it to be. Maybe for the first time, there’s a composition where you might miss something.

LL: Yeah, and then two are weird. They look fake.

RE: Oh yeah, the Buddha’s hand lemons?

LL: Yeah. It’s a mysterious film. I was talking to my psychoanalyst about it. I was telling him about [R.D. Lang’s] Knots. There’s the section I use in the film that describes this game being played, and that you’re supposed to play the game by pretending like you’re not playing the game. It’s a kind of perversity. You know, my mom is waiting for me to have this thing called fuste in Spanish, this kind of seriousness of adulthood that should click in at some point. And so as a parent, how do you teach your child to join this game of the social sphere that you

don´t want to play yourself? And in the Lucy Lippard book [I See/You Mean], there are all these possibilities of ways to play that game, or to be unable to play it.

RE: There are choices. You can harden yourself like the fake lemon, or you can get squished. And in viewing the installation you could choose not to read the text on the monitors, for example.

LL:Yeah, that’s how I wanted it to be. Maybe for the first time, there’s a composition where you might miss something.

Laida Lertxundi was born in Bilbao, Spain, and makes 16mm films primarily in and around Los Angeles, where she has lived and worked for more than a decade. Her work is intrinsically and inextricably connected to the California landscape and psyche. Beautiful and enigmatic, her 16mm films bring together ideas from conceptual art and structural film with a radical, embodied, feminist perspective.

http://laidalertxundi.com/home.html

Ren Ebel lives in Los Angeles with his wife Laida and their daughter Hanah. He is currently in the Graduate Art program at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California.

http://laidalertxundi.com/home.html

Ren Ebel lives in Los Angeles with his wife Laida and their daughter Hanah. He is currently in the Graduate Art program at ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, California.