BBQ IN BLACK

with Rubén Ortiz-Torres

DXIX: Rubén let's start by contextualizing your current show at DXIX. It is, in a way, the smallest, most condensed or “humble” solo show you’ve had in the past years in the sense that its is really a “one piece show “. You mentioned that somehow it wraps up a big body of work you have been working on in the past years.

Rubén Ortiz-Torres: This show summarizes a crossing of ideas I have been dealing with in art, life and politics. Coming this from a very baroque and scattered mind and practice I consider this an achievement more so than something “small” or “humble.” There are two different pieces in the show but they are intertwined.

It is a show that attempts to connect on one hand particular conceptual, technical, and formal issues related to painting and abstraction with politics, nationalism and iconoclasm as well as with more personal issues like immigration, my education and formation and perhaps even my relation to punk. It has to do too with negation as construction of meaning.

Rubén Ortiz-Torres: This show summarizes a crossing of ideas I have been dealing with in art, life and politics. Coming this from a very baroque and scattered mind and practice I consider this an achievement more so than something “small” or “humble.” There are two different pieces in the show but they are intertwined.

It is a show that attempts to connect on one hand particular conceptual, technical, and formal issues related to painting and abstraction with politics, nationalism and iconoclasm as well as with more personal issues like immigration, my education and formation and perhaps even my relation to punk. It has to do too with negation as construction of meaning.

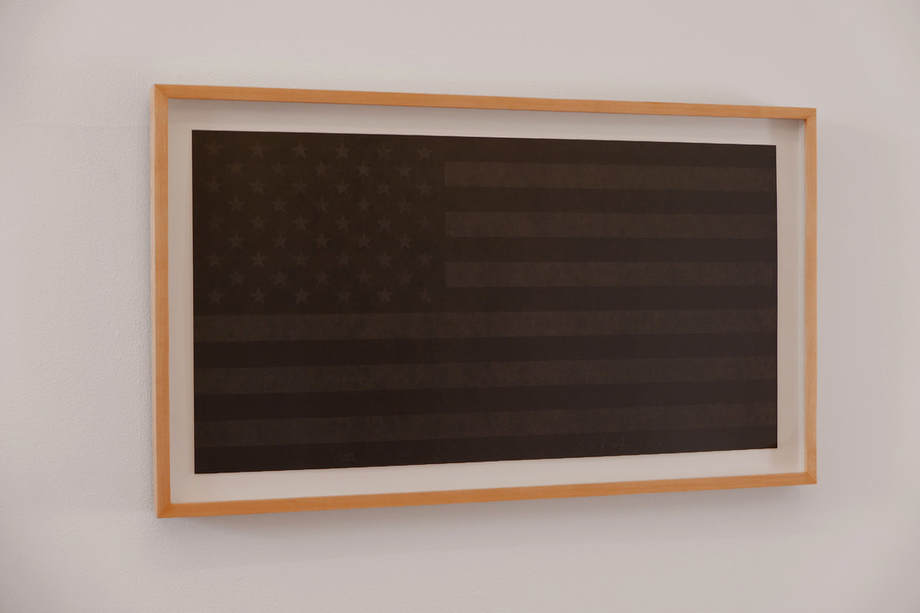

DXIX: Appropriating, referencing (and cross referencing) and reusing of your surrounding cultural vernacular and historical iconographies, the use of narratives and symbols are very common strategies in your practice. In this project we have the national flags of course, this is a very strong local referent. One can also hear echoes of the American and European Avant-garde, Goya or Baroque painting. This piece gives the impression of being very much about tracing a lineage back to the history of Painting. More specifically to the history of black paintings.

R.O-T: When I teach basic painting I have my students avoiding the use of black to force them to think about contrast in terms of color and texture and think of painting not as an extension of drawing. However I have always been attracted to Spanish painting with its dramatic use of black and darkness from the baroque of Valdez Leal to Goya, Guernica and abstract painters like Tápies and Saura. Motherwell says about his series Elegies to the Spanish Republic: “After a period of painting them, I discovered Black as one of my subjects—and with black, the contrasting white, a sense of life and death which to me is quite Spanish. They are essentially the Spanish black of death contrasted with the dazzle of a Matisse-like sunlight.”

I have been thinking of the use of black as “anti painting.” Also I have been thinking of the baroque emotional and even irrational response to the simplicity and austerity of the arguments of reason as a precedent to anti art. Of course the iconoclasm of the aesthetics of austerity could be considered also a form of anti art as well. There are also particular and interesting contradictions in the use of black in the baroque. King Philip II started in the 16th century dressing the Spanish court in black preceding existentialist, gothic and punk fashions. This was a decree of austerity by law for moral and economic reasons. However the dyes that were used to make such garments came from Mexico and were expensive making this a luxury that just few could afford.

R.O-T: When I teach basic painting I have my students avoiding the use of black to force them to think about contrast in terms of color and texture and think of painting not as an extension of drawing. However I have always been attracted to Spanish painting with its dramatic use of black and darkness from the baroque of Valdez Leal to Goya, Guernica and abstract painters like Tápies and Saura. Motherwell says about his series Elegies to the Spanish Republic: “After a period of painting them, I discovered Black as one of my subjects—and with black, the contrasting white, a sense of life and death which to me is quite Spanish. They are essentially the Spanish black of death contrasted with the dazzle of a Matisse-like sunlight.”

I have been thinking of the use of black as “anti painting.” Also I have been thinking of the baroque emotional and even irrational response to the simplicity and austerity of the arguments of reason as a precedent to anti art. Of course the iconoclasm of the aesthetics of austerity could be considered also a form of anti art as well. There are also particular and interesting contradictions in the use of black in the baroque. King Philip II started in the 16th century dressing the Spanish court in black preceding existentialist, gothic and punk fashions. This was a decree of austerity by law for moral and economic reasons. However the dyes that were used to make such garments came from Mexico and were expensive making this a luxury that just few could afford.

DXIX: Your work feels at the same time ludic and politically engaged, sarcastic and militant. Not like these things are actually opposite things but I appreciate an interest in paradox as productive space. I also find a very fertile tension in your work between mythification and demystification (some current paradigms are put in question while other less current ones are brought to front).

R.O-T: Modern art attempted to avoid the idea of representation. My conceptual teachers criticized metaphor and symbolism as connotative forms of language that depended on cultural conventions and therefore not really “objective.” However I wonder if nowadays with our practice and need of reading meaning and subtext everywhere if connotation and with it the process of mythification (in a Barthez sense) is avoidable and with it the possibility to escape metaphor, symbolism and representation. In that sense it's better to understand how these are constructed in order to use them or question them with a sense of purpose.

R.O-T: Modern art attempted to avoid the idea of representation. My conceptual teachers criticized metaphor and symbolism as connotative forms of language that depended on cultural conventions and therefore not really “objective.” However I wonder if nowadays with our practice and need of reading meaning and subtext everywhere if connotation and with it the process of mythification (in a Barthez sense) is avoidable and with it the possibility to escape metaphor, symbolism and representation. In that sense it's better to understand how these are constructed in order to use them or question them with a sense of purpose.

DXIX: Along these same lines, what is your position in relation to those, lets say, “pragmatist” modes of art practicing that advocate for implementation and intervention as the main operational strategies in order to make politically engaged or socially progressive art.

R.O-T: Art is a form of expression, a language. Once we start calling art those “pragmatic” forms of social participation and practice we subject their practical effect to one of signification. Their original purpose and function is conditioned while it drags their linguistic function. If, for Plato, art had to imitate reality now it has to be a “real” action that we have to interpret as a representation of itself. Not to even mention that artists are usually ill suited to do such actions that need expertise.

One thing is to make political art and another propaganda or politics. For some reason those differences seem to be clearer in relation to sex. We can distinguish more clearly the difference between erotic art, pornography and having sex than between political art, propaganda and politics.

R.O-T: Art is a form of expression, a language. Once we start calling art those “pragmatic” forms of social participation and practice we subject their practical effect to one of signification. Their original purpose and function is conditioned while it drags their linguistic function. If, for Plato, art had to imitate reality now it has to be a “real” action that we have to interpret as a representation of itself. Not to even mention that artists are usually ill suited to do such actions that need expertise.

One thing is to make political art and another propaganda or politics. For some reason those differences seem to be clearer in relation to sex. We can distinguish more clearly the difference between erotic art, pornography and having sex than between political art, propaganda and politics.

DXIX: You art practice has been eclectic and interdisciplinary but we can identify in the recent years of your trajectory a noticeable focus on painting. Your current paintings are very painterly but they are not conceived from a traditional “studio painter” mind set. Far from falling into purely lyrical positions or literal political commentaries you seem to manage to explore the voluptuous and expressivity of the medium while bringing to the front of the discussion historical and critical issues in relation to art and society. These paintings make “painters” happy and keep “discourse oriented audience” engaged. An interesting balance…very difficult to achieve.

R.O-T: I hope you are right. I studied art in a very traditional environment at the former "Academia de San Carlos" in Mexico City in the late eighties at a time when painting was playing an important role and then did my masters in CalArts in the early nineties. Paradoxically my peers in Mexico City often stopped painting in search of an art theory that was absent while CalArts arguably has produced some of the most interesting painting in the US almost in response to its conceptual emphasis. It seems to me that such emphasis has forced painters to use painting in a different way, to use it and think of it not as a hermetic system. Painting is just one of many tools in a toolbox with its limitations and possibilities. It is not death as long as people use it like any other language and as I can see definitely more popular than Esperanto or Latin and less threatened than indigenous languages.

R.O-T: I hope you are right. I studied art in a very traditional environment at the former "Academia de San Carlos" in Mexico City in the late eighties at a time when painting was playing an important role and then did my masters in CalArts in the early nineties. Paradoxically my peers in Mexico City often stopped painting in search of an art theory that was absent while CalArts arguably has produced some of the most interesting painting in the US almost in response to its conceptual emphasis. It seems to me that such emphasis has forced painters to use painting in a different way, to use it and think of it not as a hermetic system. Painting is just one of many tools in a toolbox with its limitations and possibilities. It is not death as long as people use it like any other language and as I can see definitely more popular than Esperanto or Latin and less threatened than indigenous languages.

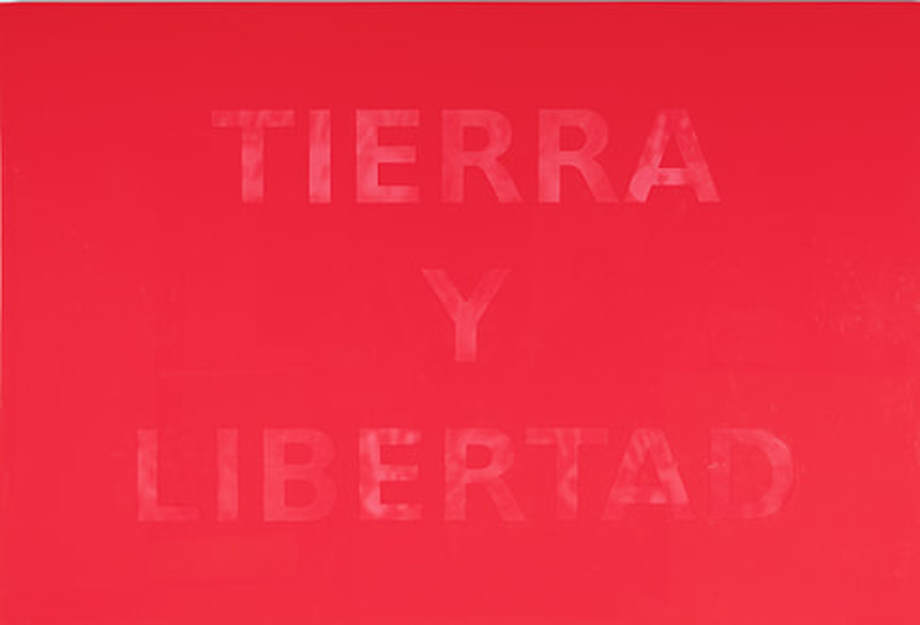

DXIX: Anarchism is a political paradigm often quite misinterpreted and a term commonly misused. The complexity and richness of its ideas and contributions to politics, education and overall culture are often undermined. Frequently simplistically and incorrectly interpreted as chaos, lack of order and destructive nihilism. What is your interest as an artist and educator in Anarchism? Where is this interest coming from? Is it your experience with ideas of the “Escuela Moderna”, your interest in Punk music? More importantly, why are you bringing this reference to the conversation now?

R.O-T: I was very lucky to study in a little experimental grammar school in Mexico City called Manuel Bartolomé Cossío. José de Tapia Bujalance who was an exiled Spanish teacher funded it. He was an anarchist who believed that to create a better, free and fair society it was necessary to start with the children. He came to Mexico as a refugee from the concentration camps in France after the defeat of democracy and the Spanish republic by Franco and its fascist forces supported by Hitler. Francesc Ferrer and his “Escuela Moderna,” Célestin Freinet and his colleague Patricio Redondo, influenced him. I loved my school. I did not know I was particularly interested in art, education and anarchism (or that other people were not) until I had to confront the limitations, rigidity, frustrations, competitiveness in opposition to collaboration, bureaucracy, hierarchic structures, etc. of other schools and society in general. So my interest comes from the real experience of an attempt of a democratic, free and self managed project that had nothing to do with “chaos, lack of order or destructive nihilism.” Obviously it was not perfect but isn’t perfection an enemy of freedom? This experience made me aware of the possibility of the possibility in a world and a country of impossibilities. In a time where the ideas of freedom and the word “libertarian” had been perverted into the possibility to exploit and abuse other people it is utmost necessary to revisit anarchist thinking.

José de Tapia told me once as I was older and visited him: “anarchism is not an A inside a circle, it is morals.”

DXIX: Where (socially, culturally) do you find these ideas “alive” right now? Where can we look in order to find current anarchist ideas at play?

R.O-T: I actually see them in lots of places. I see them in the spontaneous and independent forms of organization that mushroomed to help after the Mexico City earthquake, in the Zapatista movement, in the resurgent Chicano interest in the Flores Magón brothers, in the DIY spirit of punk, the Riot Girls, in Occupy Wall Street, in the open programs of contemporary art education, the writings of Chomsky, artist run organizations, in thriving cooperatives, in non linear and open digital systems, in the rhizome, etc. I also see a similar spirit in ideas that might even precede anarchist thinking such as certain Pre Columbian indigenous forms of organization like the “Tequio.” Even the utopian dreams of Jefferson and Marx coincided in self governed free and fair societies.

R.O-T: I actually see them in lots of places. I see them in the spontaneous and independent forms of organization that mushroomed to help after the Mexico City earthquake, in the Zapatista movement, in the resurgent Chicano interest in the Flores Magón brothers, in the DIY spirit of punk, the Riot Girls, in Occupy Wall Street, in the open programs of contemporary art education, the writings of Chomsky, artist run organizations, in thriving cooperatives, in non linear and open digital systems, in the rhizome, etc. I also see a similar spirit in ideas that might even precede anarchist thinking such as certain Pre Columbian indigenous forms of organization like the “Tequio.” Even the utopian dreams of Jefferson and Marx coincided in self governed free and fair societies.

DXIX: Visual arts, opera, music, teaching, curating, writing.... Once you told me (more or less) that you rather wear many hats even at the risk of eventually not advancing as far as you could in each particular area. You also told me you that when you began your education you didn't specifically want to be an artist but you ended up becoming one because it allowed you to do all sorts of things and engage in many different conversations at the same time. This reminds me of that metaphor that describes the difference between the one who wants to find the most efficient way to get to the top of a mountain in order to see the vista (but misses most of the mountain) and the one who prefers to wander around the mountain in order to explore its different corners at the risk of never getting to the top. Both are very different ways to experience and live the mountain. Along these lines I can't help but thinking about Luis Bunuel; an artist and figure that we both admire. When reading his biography “Mi ultimo suspiro” I had the feeling Bunuel made films, wrote, and engaged in other creative adventures just as a way of engaging with life in certain way. Looking for discovering in life and living it fully. I don't think he ever had a deliberate plan to make art even if he couldn't really live without making it.

R.O-T: I actually love the metaphor. Why should the vista of the top be worth more than the different corners? Perhaps the problem of coming from such an open educational system that fosters a wide range of interests is not the lack of focus but the realization of the many things worthy of a focus.

It has been a complicated issue to describe my practice and the lack of a homogeneous single body of work. Especially at the beginning of my career when more modernist curators and gallerists used to interpret that as a lack of maturity. Nowadays I get similar complicated responses when I ask my scientist colleagues at the university what do they do. They often have interdisciplinary careers that intersect different sciences and practices such as chemistry, physics, medicine, engineering, biology, etc.

I see Buñuel with the moral envy and respect I have for my teacher José de Tapia, my father and my grandfather. He was able to produce the most radical avant-garde in the center as well as far away from it, while having a family and without making compromises. He teaches us not that “life is art” but that you have to have a life to make art.

R.O-T: I actually love the metaphor. Why should the vista of the top be worth more than the different corners? Perhaps the problem of coming from such an open educational system that fosters a wide range of interests is not the lack of focus but the realization of the many things worthy of a focus.

It has been a complicated issue to describe my practice and the lack of a homogeneous single body of work. Especially at the beginning of my career when more modernist curators and gallerists used to interpret that as a lack of maturity. Nowadays I get similar complicated responses when I ask my scientist colleagues at the university what do they do. They often have interdisciplinary careers that intersect different sciences and practices such as chemistry, physics, medicine, engineering, biology, etc.

I see Buñuel with the moral envy and respect I have for my teacher José de Tapia, my father and my grandfather. He was able to produce the most radical avant-garde in the center as well as far away from it, while having a family and without making compromises. He teaches us not that “life is art” but that you have to have a life to make art.

DXIX: Finally, talking about life and art. A few decades ago you arrived to Southern California and for one reason or another you ended up staying. Looking back to the work you have produced and the projects you have been involved with looks like the SO CAL cultural ecosystem and Rubén Ortiz-Torres are what some would call a “match made in heaven”. Was this a process or a love at first sight? Why settling here instead of other places like CDMX, NYC or Europe. On a general note, any comments on the recent evolution of the Los Angeles art scene? It looks like the international attention and the global influx of art agents and capital is bigger than ever. Rents and taco prices are going up too...

R.O-T: LOL… I wonder about this “match made in heaven” theory. It was certainly not a love at first sight. In fact the first time I came here in 1972 I did not even notice there was a city between LAX and Disneyland.

With the PST initiatives I have had to seriously articulate and think my relationship to Southern California. I wrote extensively about it in the catalogs of “MEX/LA, ‘Mexican’ Modernism(s) in Los Angeles 1930-1985” and “How To Read el Pato Pascual.” For me LA has not been an option instead of Mexico City and New York or Europe but in fact the possibility to be somewhere in between or in both. Somewhere where I could be in Mexico when I need to or want to and where I could be also in the first world or close to it with access to New York and/or Europe when necessary.

By the time I got here, Southern California was already the capital of popular culture and contemporary art education but was still needy of the validation of a New York more interested in its nostalgia for the factory and the CBGB and in confirming its Annie Hall stereotypes of “La la land.” MOCA for example would import Mexican art from New York incapable of recognizing the city’s cultural production signaling a failure as a cultural center. The art scene in California was (and still is) less commercial and dependent on the market and more related to education and academic research. However with all its problems it was clear the region was maturing. Certain efforts are worth mentioning like Gary Kornblau’s “Art Issues” magazine. It addressed culture and art in a serious and inclusive way. The PST initiatives funded and helped the creation of a more competitive and open way to do research and present art. Add to this the resources of the film industry, the proximity to Silicon Valley and with it access to new technologies, the car and aerospace industries and very importantly the proximity to the border and the port making it the gate to immigration, imports and to the world and you get a recipe for a thriving center of art production. Distribution is starting to come after this. Let’s hope that rents and the cost of living still allow this to happen.

R.O-T: LOL… I wonder about this “match made in heaven” theory. It was certainly not a love at first sight. In fact the first time I came here in 1972 I did not even notice there was a city between LAX and Disneyland.

With the PST initiatives I have had to seriously articulate and think my relationship to Southern California. I wrote extensively about it in the catalogs of “MEX/LA, ‘Mexican’ Modernism(s) in Los Angeles 1930-1985” and “How To Read el Pato Pascual.” For me LA has not been an option instead of Mexico City and New York or Europe but in fact the possibility to be somewhere in between or in both. Somewhere where I could be in Mexico when I need to or want to and where I could be also in the first world or close to it with access to New York and/or Europe when necessary.

By the time I got here, Southern California was already the capital of popular culture and contemporary art education but was still needy of the validation of a New York more interested in its nostalgia for the factory and the CBGB and in confirming its Annie Hall stereotypes of “La la land.” MOCA for example would import Mexican art from New York incapable of recognizing the city’s cultural production signaling a failure as a cultural center. The art scene in California was (and still is) less commercial and dependent on the market and more related to education and academic research. However with all its problems it was clear the region was maturing. Certain efforts are worth mentioning like Gary Kornblau’s “Art Issues” magazine. It addressed culture and art in a serious and inclusive way. The PST initiatives funded and helped the creation of a more competitive and open way to do research and present art. Add to this the resources of the film industry, the proximity to Silicon Valley and with it access to new technologies, the car and aerospace industries and very importantly the proximity to the border and the port making it the gate to immigration, imports and to the world and you get a recipe for a thriving center of art production. Distribution is starting to come after this. Let’s hope that rents and the cost of living still allow this to happen.

Ruben Ortiz-Torres was born in Mexico City in 1964. Educated within the utopian models of republican Spanish anarchism soon confronted the tragedies and cultural clashes of post colonial third world. Being the son of a couple of Latin American folklore musicians he soon identified more with the noises of urban punk music. After giving up the dream of playing baseball in the major leagues, and some architecture training (Harvard Graduate School of Design) he decided to study art. He went first to the oldest and one of the most academic art schools of the Americas (the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City) and later to one of the newest and more experimental (Calarts in Valencia CA). After enduring Mexico City's earthquake and pollution he moved to Los Angeles with a Fullbright grant to survive riots, fires, floods, more earthquakes, and proposition 187. During all this he has been able to produce artwork in the form of paintings, photographs, objects, installations, videos, films, customized machines and even an opera. He is part of the permanent Faculty of the University of California in San Diego. He has participated in several international exhibitions and film festivals. His work is in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Artpace in San Antonio, the California Museum of Photography in Riverside CA, the Centro Cultural de Arte Contemporaneo in Mexico City and the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid Spain among others.

After showing his work and teaching art around the world, he now realizes that his dad's music was in fact better than most rock’n roll.